The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844: The Streets of Filth

Friedrich Engels’ The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844 offers a powerful and unfiltered examination of the profound social upheavals wrought by the Industrial Revolution in Manchester.

Engels’ work is not simply a historical account but a moral indictment of the economic structures that facilitated such vast inequalities. His observations reveal the human cost hidden behind the rise of industrial capitalism, providing a searing critique of a society that privileged profit over human welfare.

Manchester, in the mid-1800s, was a city transformed almost beyond recognition. Engels captures this transformation with precise detail: "Manchester lies at the foot of the southern slope of a range of hills, which stretch hither from Oldham" and comprised a sprawling urban population of about four hundred thousand people (Engels, 1950, p. 11). The city’s rapid expansion reflected the influx of labour necessary to fuel its industrial engines, a growth which strained all aspects of urban life and infrastructure.

In the cramped quarters of the working class, Engels found spaces barely fit for habitation.

Rooms no larger than five feet by six feet, packed with beds and lacking basic amenities, were the norm rather than the exception (Engels, 1950, p. 32). The physical confines of these dwellings were indicative of a broader social confinement, where workers were trapped in cycles of exploitation and deprivation.

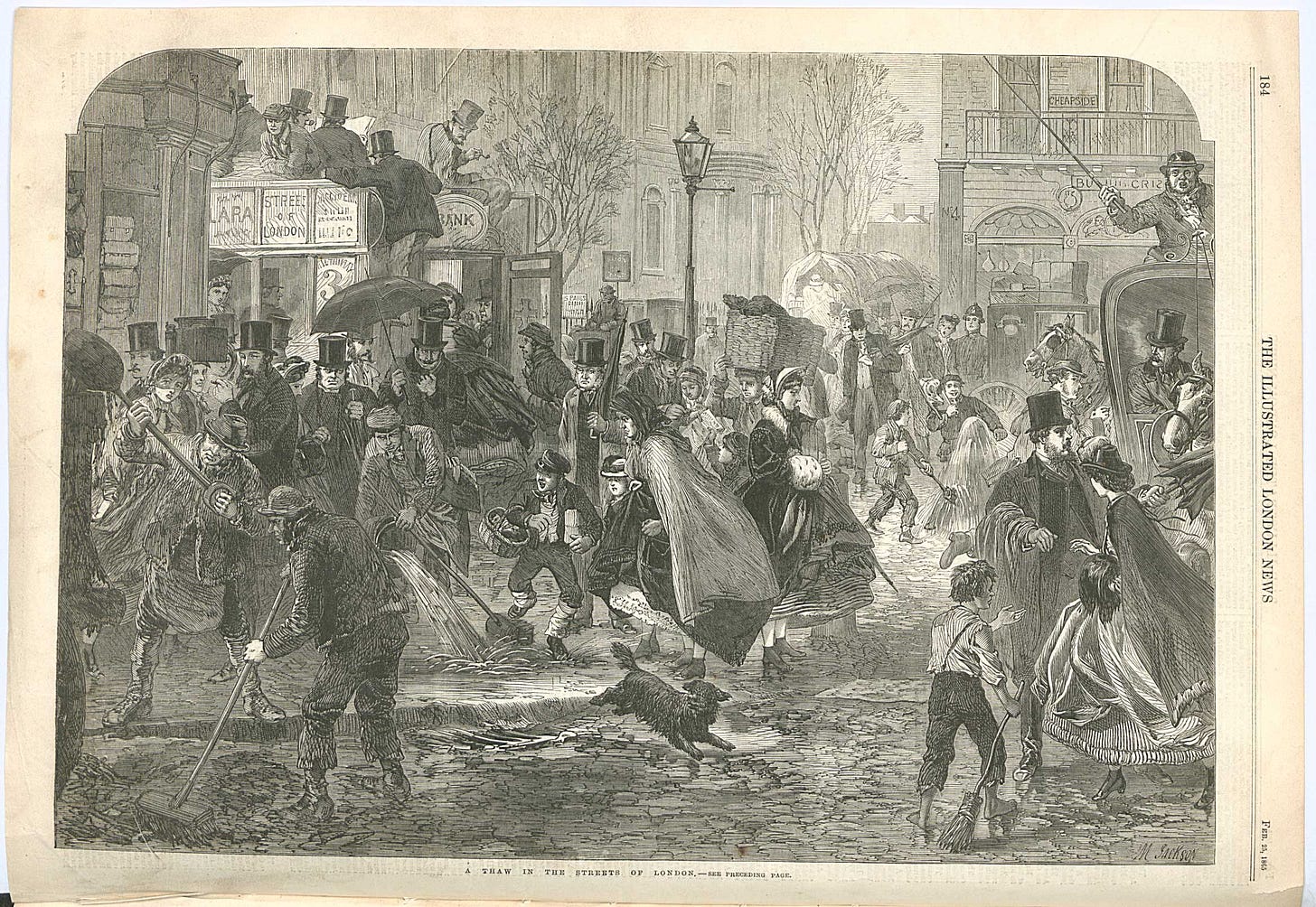

The division of Manchester into starkly segregated districts was emblematic of the new social order. Engels emphasizes that the quarters of the working people were sharply divided from those of the middle class (Engels, 1950, p. 43). Such spatial segregation was deliberate, a physical manifestation of class divisions, with the working class relegated to decaying, narrow streets while the wealthy inhabited spacious, well-maintained areas.

One cannot overstate the horror of the sanitation conditions.

Engels describes privies without doors, where passage through courtyards necessitated crossing pools of stagnant urine and excrement (Engels, 1950, p. 50). The filth and neglect were systemic, borne from an economic system that viewed workers as mere cogs in the machine, dispensable and unworthy of basic hygiene or health considerations.

Historians such as E.P. Thompson have echoed Engels’ insights, illustrating the industrial city as a place where capitalist imperatives routinely undermined worker health and safety (Thompson, 1963). Public health scholars further document how nineteenth-century industrial urban centres were landscapes of environmental injustice, disproportionately burdening the poor with pollution and disease (Jackson, 2000). Engels’ vivid account of the Irk River, described as "a narrow, coal-black, foul-smelling stream, full of debris and refuse," stands as a grim symbol of this environmental degradation (Engels, 1950, p. 54).

Industrial capitalism, Engels argues, not only degraded bodies but corroded communities and moral life.

The social fragmentation it produced was as corrosive as the pollution poisoning the city’s waterways. He asserts that all the horrors and indignities of Manchester were products of the industrial age, signaling a profound moral crisis (Engels, 1950, p. 56).

Engels did not resign himself to mere description; his writing carries the urgent imperative for social reform. The overcrowding, filth, and misery he describes were not unfortunate by-products but consequences of a capitalist economy prioritizing accumulation over human dignity. His socialist convictions are apparent in his vision for structural change, championing worker emancipation and social justice.

The dynamics Engels observed continue to inform contemporary analyses. David Harvey conceptualizes early industrial cities as sites of “accumulation by dispossession,” where working-class communities were systematically marginalized and deprived of resources essential for wellbeing (Harvey, 2003). Public health experts like Sally Sheard illustrate how the urban poor suffered disproportionately from infectious diseases linked to overcrowding and poor sanitation, highlighting enduring social determinants of health (Sheard, 2013). Engels’ observations remain vital to understanding the roots of these patterns.

Joel Tarr situates Manchester within a broader urban crisis, where infrastructural failures and political neglect compounded the suffering of industrial populations (Tarr, 1996).

The city becomes a microcosm of power struggles, where governance often served the interests of industrial capitalists at the expense of public welfare.

The psychological toll of such conditions is significant. Engels’ descriptions anticipate Georg Simmel’s concept of the “blasé attitude,” a psychological adaptation to the relentless stimuli and alienation of urban modernity (Simmel, 1903). The social alienation, despair, and social ills Engels observed were not incidental but entwined with the material conditions imposed on the working class.

Women and children faced compounded burdens. Engels’ observations foreshadow feminist critiques that reveal how industrialization intensified gendered inequalities, forcing women to juggle paid factory labour and domestic responsibilities amid abject living conditions (Rowbotham, 1973). Such intersectional hardships complicate simplistic class analyses and highlight the multifaceted nature of industrial oppression. Joan Scott’s intersectional approach deepens this analysis, exploring how class, gender, and race coalesced to shape experiences within industrial cities (Scott, 1999). Engels’ work provides the foundation for these nuanced perspectives, revealing the layered complexities of oppression.

Engels’ The Condition of the Working-Class in England endures as a crucial historical document and moral critique.

His depiction of Manchester’s “streets of filth” challenges modern readers to reflect on the ethical costs of economic progress and the persistent legacies of inequality. The call for reform that resonates through his pages is as urgent today as it was in the nineteenth century.

The conditions Engels describes are not confined to history. Across the globe, contemporary urban centres reflect similar patterns of segregation, environmental harm, and social neglect. His work remains a cautionary tale about the consequences of economic development divorced from social responsibility.

Ultimately, Engels’ meticulous documentation serves as a powerful reminder. Economic growth that ignores human dignity is a path fraught with suffering. The history of Manchester’s working class offers lessons vital to building more equitable and humane societies.

References

Engels, F. (1950). The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Harvey, D. (2003). The New Imperialism. Oxford University Press.

Jackson, S. (2000). Social Justice and Public Health. Oxford University Press.

Sheard, S. (2013). The Origins of Public Health and the Modern City. Routledge.

Thompson, E.P. (1963). The Making of the English Working Class. Vintage.

Tarr, J. (1996). The Search for the Ultimate Sink: Urban Pollution in Historical Perspective. University of Akron Press.

Simmel, G. (1903). The Metropolis and Mental Life. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel (translated and edited by Kurt Wolff). Free Press, 1950.

Rowbotham, S. (1973). Hidden from History: 300 Years of Women’s Oppression and the Fight Against It. Pluto Press.

Engels, F., & Rosemont, F. (2001). Engels on Women, the Family and Sexuality. Pathfinder Press.

Scott, J.W. (1999). Gender and the Politics of History. Columbia University Press.

Jeff,

What you’ve presented here is not merely a reflection on the past—it is a mirror held up to consciousness itself. The soot-stained streets, the cries of the neglected, the cramped corridors of the forgotten—these are not just historical facts; they are out-pictured states of consciousness, made visible by the collective assumption of lack, hierarchy, and disconnection.

Engels documented what man imagined unconsciously. You, through this work, call us to imagine consciously.

The lesson is not just in the horror, but in the power: the world reshapes itself by what man dares to assume as real. When we imagine dignity, structure bends toward justice. When we assume worth, systems begin to serve life.

This piece isn’t only a reading of history—it’s an invitation to rewrite the future through the only true cause: our inner state.

With respect,

Kurt Juman

in the spirit of Neville Goddard

And sadly this template can be seen across the globe throughout the times. You can still see this in many places. Or at least the remnants. The chawls and slums of Mumbai were one such place. They still exist. But some of not most now pretend to be a lot poorer than they are. To avoid climibing the "ladder" to middle class. Where you have to pay maintenance fees and taxes and be formalised into the economy. But I'm veering off topic.

The cost of "progress" I guess